Are classical musicians excluded from improvisation? Cultural hegemony and the effects of ideology on musician's attitudes towards improvisation.

Abstract:

Since the late 18th century, and the flowering of Romanticism, western classical or ‘art’ music has often striven to express ‘the great sublime in nature’ (Burke, 1757). However, though a source of inspiration and motivation for creative expression, the rise of romantic aesthetics has restricted the creative freedom of classical musicians. Attitudes of Werktreue now form the implicit goals of many western classical music institutions which, over 200 years have suppressed improvisation and focused the curriculum of musical education almost exclusively upon interpretive performance. This curriculum not only leaves many classical musicians without the skills of improvisation, but also promotes certain values and beliefs about classical music itself (that it must be composed, not improvised), and about their role as interpretive performers (that they intrinsically lack the skills, or the right, to create their own ‘classical’ music). In this article I turn to the writing of Althusser (1971) to illustrate how implicit values and beliefs within the cultural institutions of classical music create a hegemonic control over musical practice. As a result classically-trained musicians are excluded from improvisational practices, because: (i) individuals must act within a culture in which improvisation itself is excluded, and (ii) implicit ideals about how music is created and who creates it discourage create emotional and cognitive barriers to the acquisition of improvisational skills.

Accepted for publication in Contemporary Music Review, 2020 (in press).

Mobilising improvisation skills in classically-trained musicians

Abstract:

There are relatively few classical musicians who learn to improvise. In this study the author reports on his own experience of overcoming former training in interpretive performance to learn how to improvise on Baroque models of composition. Cognitive and emotional ‘barriers’ to improvising are identified and learning strategies described through which the author gained new insights into musical structure enabling him to see ‘beyond the score’. Based on an autoethnographic account, this chapter is a reflective and personal exploration of knowledge and skill acquisition which aims to motivate others to mobilise their own learning. Suggestions are also made for teaching improvisation which conclude that a student-based, supportive, and flexible approach is more effective than general pedagogic methods and prescribed exercises.

Book chapter (in press)

In, Sound Teaching: A research-informed approach to vocal and instrumental music (Henrique Meissner, Renee Timmers, Stephanie Pitts, Eds.). Taylor & Francis/Routledge.

Why don't classical musicians (learn to) improvise?

An open-source article. Download here

Abstract:

1. Introduction.

It is often stated that, in spite of a rich historic improvisational activity, classical musicians no longer improvise. But how can this statement be understood? If musicians don’t improvise, why

not? Who makes the decision? Is a decision in fact made?

In the first part of this essay I examine these questions by looking at the practice of classical music from an ideological perspective. To understand how, in general, people can be persuaded to act in certain ways, without compromising their own individual will, it is necessary to conceptualise the practice of classical music as a cultural institution with it’s own ideology - a set of commonlyheld beliefs which are implicitly reinforced rather than explicitly stated. Statements and texts, programming and practice in general, I conclude reveal hidden or implicit beliefs about music, beliefs which prevail against the expression of natural appetites to improvise. In the second section, I consider the specific ideology - the collection of beliefs - which guides the practice of classical music. In this respect I am heavily indebted to Goehr’s (1994) rich and insightful analysis of musical practice, which charts the birth of the work-concept or Werktreue ideal, now central to modern music-making. As the word implies, the Werktreue ideal, proposes that musicians be true or faithful to the created work, or score. Of critical importance to the Werktreue ideal is the belief that scores themselves represent the transcendental creative act of a composer - a belief which has led to attitudes of reverence towards scores and a division of labour amongst musicians between composers who create original works, and performers who specialise in interpreting such works. I conclude with an analysis of the Werktreue principle in relation to improvisation, showing how this principle with its associated ideology removes the contexts in which improvisation can be practised and learnt. In the third part of the essay I address the fact that, for musicians steeped in the ideology of

the Werktreue principle, the transition to improvising is not a comfortable or straightforward one, requiring considerable changes of attitude and beliefs. I examine literature in the fields of learning, attention, role models and personality types to illustrate some of the emotional barriers which await the experience of classically-trained musicians as they attempt to improvise. In spite of much recent literature which examine improvisation from a range of perspectives, there is little consideration given to the emotional aspects of learning, yet I believe it is unlikely that musicians will succeed in developing the cognitive skills of improvisation if their experience is valenced towards negative feelings of frustration, shame and embarrassment.

Caleidoscópio - Música na primeira pessoa

A series of thirteen radio programmes written for RDP Antena 2 (the national classical music radio station for Portugal), which explore many aspects of improvising and learning to improvise.

All programmes are available online: https://www.rtp.pt/play/p330/e489502/caleidoscopio

The series is written as a collection of personal biographical narratives, each giving a different perspective on improvisation. Life at an english boarding school, training as a young musician in interpretive performance, starting a career as a freelance musician in London during the 1990s are themes which gradually give way to more detailed explorations of improvisation: what is it like to improvise a fugue? how does the knowledge and experience of an improviser differ from that of the score-reading interpreter? what are the risks of improvising in public? what are the benefits of learning to improvise?

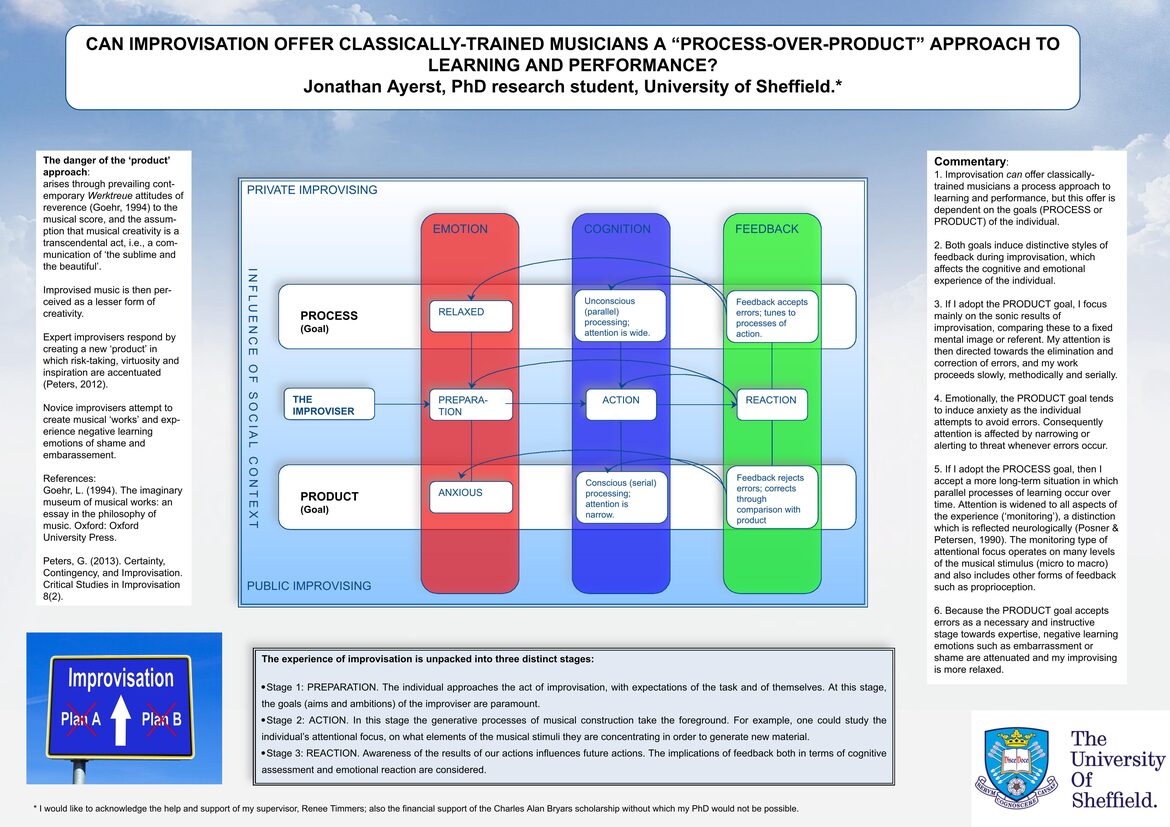

Can improvisation offer classically-trained musicians a 'process-over product' approach to learning and performance?

Poster presented at the International Symposium on Performance Science, Reykjavik, Aug-Sep,2017

Background

Current musical practice is still largely dominated by aesthetical visions of the 18th Century (i.e. the sublime and the beautiful). Reinforced by social changes, in particular the rise of the middle classes during the 19th century, and widespread technological and media influence during the 20th, such visions associate musical creativity with a transcendental act of composition: composers aspire to both emulate and overcome the genius and originality of natural forces in their production of musical products or works. Performance has risen to the challenge of interpreting the

content of such products with the ideals of Werktreue: the accurate and transparent rendition of scores. As such, musical practice can be divided into those that compose and those that interpret; both paths of development being dominated by the idea of rigidity—that communication is the successful transmission of fixed formal elements in a score. Improvisation offers a middle road between the two poles of composition and interpretive performance; it offers the performer a share in the creative process, a new perspective to listeners of classical music being live process rather than a reflection on past products, and a different learning experience to students. However, little is known about the learning processes of improvisation and compared to other art forms, classical music is marked by a rarity of improvisational practice, both in performance and learning.

Aims

The principal aim of this paper is to offer psychological insights into the experience of learning to improvise as a classical musician. While learning, I understood that many of the cognitive and emotional barriers to improvisation occur because of one’s training as a classical musician—a training which places the products of others’ creativity at the center of practice. Improvisation offers a challenge to classically-trained musicians to adopt a process-orientated approach to music, but it is a perspective which is not automatically learnt through improvising. My further aim therefore is to make explicit the learning techniques necessary to acquire a process-based approach to improvisation.

Main contribution

(1) To outline the development of attitudes towards creativity which result in an ideology which reifies music as a product. On the acceptance of ideology functioning psychologically to govern cultural practice, improvisation can be seen to have no intrinsic rationale within this practice, unless as a secondary form of creativity.

(2) I review and criticize contemporary models of classical improvisation which promote improvisation as a product,

rather than a process.

(3) I clarify the principal differences in learning and performance techniques between a product and a processorientated approach towards improvisation. These include areas such as attentional focus, clarifying extrinsic and intrinsic goals, monitoring feedback, and managing task constraints.

Implications

The present study represents the first steps towards a pedagogy, based in psychology, which makes explicit a process based approach towards improvisation. Such a pedagogy, if brought to fruition, could potentially encourage many musicians to engage in improvisation, who, because of implicitly learnt assumptions about musical practice, are emotionally and cognitively barred from any such creative practices.

Please scroll down for a range of different articles and presentations about improvisation